Reblog – Behavioural finance: Money illusion

Money illusion describes the tendency of people to think about money in nominal rather than in real or inflation-adjusted terms. In other words, it’s when people focus on the absolute amount of money rather than what that money can buy.

The concept of money illusion was first discussed by Irving Fisher and later popularised by John Maynard Keynes. Fisher defined it as “the failure to perceive that the dollar, or any other unit of money, expands or shrinks in value”.

In behavioural psychology terms, the issue of money illusion is an example of a broader cognitive failing known as frame dependence where perceived losses tend to have undue prominence in our decision-making.

One classic behavioural finance text showing the existence of money illusion was written by Shafir, Diamond and Tversky in 1997. It was based on experiments and real situations. Participants, for example, were presented with the following scenario:

Imagine that Adam, Ben and Carl each receive an inheritance and buy houses for $200,000. Each sells their house one year later, but under different economic conditions. Adam sells his house for $154,000, 23% less than what he paid for it. When Adam owned the house there was 25% deflation. Ben sells his house for $198,000, 1% less than what he paid for it. When Ben owned the house, there was no change to prices. Carl sells his for $246,000, 23% more than he paid for it. When Carl owned the house there was 25% inflation.

When subjects were asked to rank these transactions in terms of success, the results showed that they were influenced by nominal values. The majority of subjects (60%) ranked Carl as having done best, Ben second and Adam third.

In real terms, the reverse is true. Adam did best because he made a real gain of 2%. Ben did second-best, making a nominal and real loss of 1%. Finally, Carl did worst, making a real loss of 2%.

The behavioural explanation for money illusion suggests that people’s thinking is driven by automatic, emotional reactions to the perceived changes in nominal values. While the calculation to account for inflation is not difficult, it involves an extra step and at least part of the brain seems strangely anchored to nominal values.

There are financial implications with this. One of the key problems is the situation where nominal increases in income are mistaken for genuine gains in purchasing power, when inflation may be diminishing the real worth of money. In fact, money illusion has been cited as why small levels of inflation are desirable for economies at least in terms of earnings growth. Having low inflation allows employers to modestly raise wages in nominal terms without necessarily paying more in real terms. As a result, many people who get pay increases make the mistake of thinking their wealth is rising, since they fail to adequately account for inflation.

In periods of rising inflation, income and prices tend to be correlated and there have been wage-price spirals where the two factors feed off each other. In periods of deflation, in theory, the process should work in reverse with downward wage price spirals, but in reality this tends not to happen. The reason is that labour is resistant to nominal wage decreases, partly due to money illusion. Unemployment tends to be the outcome because firms react to falling prices and declining profits by cutting staff.

In investment, the challenge is to make a real return on an outlay. If inflation is 3% and your investment gives you 5%, the real return is 2%. With the ability of inflation to act as a tax that erodes purchasing power over time, the best way to counteract inflation is to invest money in assets that can provide a return above inflation.

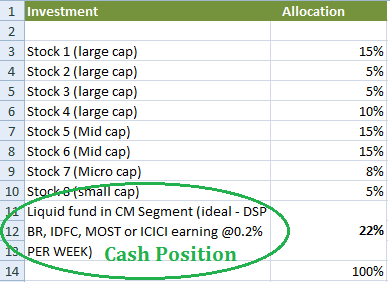

With record low interest rates, keeping money in a bank account or a money-market fund may not generate enough return to keep pace with even moderate inflation.

Despite this, the evidence suggests investors are more averse to nominal risks than real ones. Consider the “flight to safety” that occurs during most economic and stock-market downturns. Investors flood into safe assets such as bonds, which do not keep pace with inflation, while ignoring equities, despite the fact they may have cheapened considerably.

While the idea of holding cash may be emotionally appealing as it feels like a safe trade in nominal terms, such conservatism runs the risk of reduced purchasing power.

Assuming we do not strike deflation, in the prevailing environment of historically low interest rates, some analysts believe that cash and government bonds run the risk of providing negative real returns. This is encouraging many investors to look for real returns in high-yield bonds, real estate and equities.

Investors with a time horizon of five or more years should consider shifting surplus cash into assets where there is a prospect of a real return. Equities can offer attractive inflation-proofing characteristics as many companies can pass price increase onto consumers to protect their profits.

The original article appears on bull.com.au and appears here.