Reblog: Risk Is Not High Math

Smead Capital Management letter to investors titled,”Risk Is Not High Math.”

Long term success in common stock ownership is much more about patience and discipline than it is about mathematics. There is no better arena for discussing this truism than in how investors measure risk. It is the opinion of our firm that measuring a portfolio’s variability to an index is ridiculous, because it is impossible to beat the index without variability.

We believe that how you measure risk is at the heart of how well you do as a long-duration owner of better than average quality companies. In a recent interview, Warren Buffett explained that pension and other perpetuity investors are literally dooming themselves by owning bond investments that are guaranteed to produce a return well below the obligations they hope to meet.

Buffett defines investing as postponing the use of purchasing power today to have more purchasing power in the future. For that reason, we see the risk in common stock ownership as a combination of three things; What other liquid asset classes can produce during the same time period, how the stock market does during the time period, and how well your selections do in comparison to those options. Why would professional investors mute long-term returns in a guaranteed way? The answer comes from how you define risk.

Defining Risk

College finance professors, Morningstar and most of the professional investment consulting community define risk via “high math.” Risk to them is measured by how much your results vary from the stock market averages each year. They call it the standard deviation and they utilize fancy mathematical equations for measurement. Here is their argument: “if I am going from point A today to point B in ten years, it is less risky to get there if the variability of the portfolio is at a minimum.”

This runs completely contrary to what the best academic evidence shows in relation to firms which have beaten the S&P 500 Index over long stretches of time. It also helps to explain why The Wall Street Journal recently criticized Morningstar’s manager research. Martin Cremers, in his academic work, proves that it is impossible to outperform the index if you don’t assume significant variability, because outperformance is varying. One way of thinking about outperformance is you must be a “deviant.” Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger remind everyone that if you wouldn’t be willing to own part of a company 50% cheaper than where it is today, you shouldn’t own it at all. Short-term variability is a given to the greatest stock picking team of all time.

To us, common stock ownership risk lies in the following facts. First, people are considered great stock pickers if they are right about 60-65% of the time over the long haul. Therefore, short-term variability comes when the poor choices are dominating temporary results, rather than the best selections. We have a long-time friend who reminds us that on the stock purchases which go up many times your money over ten to twenty years, it didn’t make much difference what you paid to buy them during the early years.

Therefore “low math” dominates successful investing. If you buy a stock and pay cash, your risk is finite (dropping to zero). Your upside is pretty much unlimited. We like to say that long-term stock price winners cover a multitude of poor performers the same way that love covers a multitude sins in the Bible. This is true for both growth and value investors.

Second, among liquid asset classes, stocks outperform over longer time frames, but not necessarily over the next couple of years. The fact that we don’t get to know how results are delivered is exactly why you get rewarded for taking the risk. This is a fact best left to the end owners, not to the stock picker.

Third, the risk inherent in owning stocks for a long time is designed to get you the reward of more purchasing power than you would have had otherwise. Emphasizing variability/standard deviation is saying that the ride is more important than the result, and that is exactly what Buffett was chiding pension investors for doing. It is impossible to own stocks without accepting the ups and downs and it is academically impossible to outperform without significant variability. It is why Cremer’s work shows that high conviction/concentrated and low-turnover portfolio disciplines are the ones which add alpha and outperform the S&P 500 Index.

Fourth, measuring risk by variability really says way more about investors and human psychology than it does about stock pickers. Do you pay a consultant to tell you that it can be hellaciously cold in Minnesota in the winter or that it is unbearably hot in July in Phoenix and Houston? You don’t get to know which days are the hottest or the coldest, the residents don’t make any effort to predict it and it does not influence their decision to live there.

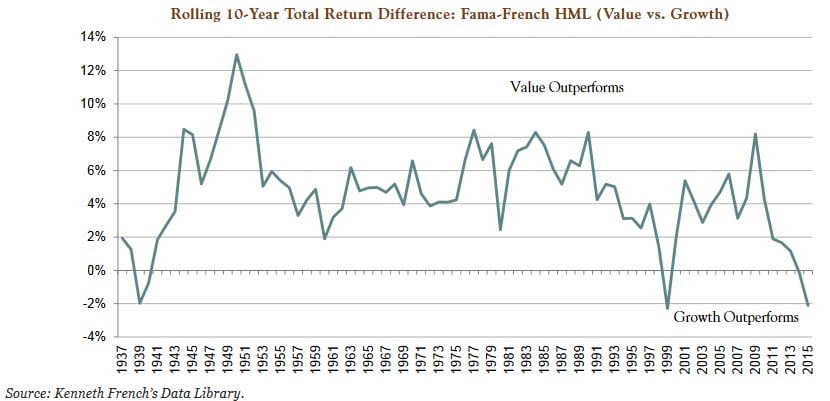

Lastly, we believe that inconsistency is a much greater risk to investors than uncontrollable variability. When a portfolio underperforms, is it because of a break away from the normal discipline or the natural result of the temporary circumstances outside the control of the discipline? We always explain to potential investors the circumstances surrounding our bouts of underperformance. Our tendency is to not do well when commodity-driven and capital intensive/labor intensive businesses lead the market for extended time periods. We also tend to underperform in years when expensive glamour growth stocks are all the rage. We are in the third biggest growth stock outperformance period in the last 80 years as seen in the chart below:

Source: Dodge & Cox, April 2016; Kenneth French’s Data Library

Since growth has stomped value over the last ten years and the S&P 500 Index has produced a positive return for nine consecutive years, consultants like Morningstar have effectively begun to ask for something which can’t happen. They are asking for outperformance with low variability. This is like asking for 80-degree weather in July in Phoenix and for balmy weather in Minneapolis in the dead of winter. Using our strategy as an example, Morningstar considers our discipline “high” risk even though we beat the S&P 500 Index for seven out of the ten years of its existence and beat the Russell 1000 Value Index in its first ten years.

In conclusion, we believe a major reassessment needs to occur in how investors measure risk while the current bull market lasts. Mindless passive investing works great when the index has a positive return for nine years in a row, is dominated by glamour growth stocks, and variability seems to have disappeared from long-duration common stock ownership. In the next ten years, we are devoted to adding alpha despite what is likely to be a stock market which gets re-introduced to volatility and variability itself. And our opinion doesn’t need “high math.”

Warm regards,

William Smead

The original post appeared on valuewalk.com and is available here.