Reblog: A Little Knowledge is Dangerous

20How to Deal with Overconfidence in Financial Markets

It had been a little over a week since anyone had seen Karina Chikitova. The forest she had walked into nine days prior was known for being overrun with bears and wolves. Luckily, she was with her dog and it was summer in the Siberian Taiga, a time when the night time temperature only dropped to 42 degrees (6 Celsius). However, there was still one major problem — Karina was just 4 years old.

Despite the odds against her survival, Karina was found two days later after her dog wandered back to town and a search party retraced the dog’s trail. You might consider Karina’s 11 day survival story a miracle, but there is a hidden lesson beneath the surface.

In his book Deep Survival: Who Lives, Who Dies, and Why, Laurence Gonzales interviews Kenneth Hill, a teacher and psychologist who manages search and rescue operations in Nova Scotia. When Gonzales asks Hill about those who survive versus those who don’t, Hill’s response is surprising (emphasis mine):

It’s not who you’d predict, either. Sometimes the one who survives is an inexperienced female hiker, while the experienced hunter gives up and dies one night, even when it’s not that cold. The category that has one of the highest survival rates is children six and under…And yet one of the groups with the lowest survival rates is children ages seven to twelve.

So why do younger children fare better in survival situations than their slightly older counterparts? Gonzales attributes this to their lack of brain development:

For example, small children do not create the same mental maps adults do. They don’t understand traveling to a particular place, so they don’t run to get somewhere beyond their field of vision. They also follow their instincts. If it gets cold, they crawl into a hollow tree to get warm. If they’re tired, they rest, so they don’t get fatigued. If they’re thirsty, they drink. They try to make themselves comfortable, and staying comfortable helps keep them alive.

Karina displayed these exact behaviors when she became lost. She hid in tall grasses away from animals, she curled up with her dog to stay warm, and she found berries to eat when she was hungry. Contrast this with Gonzales’ description of Karina’s slightly older counterparts (emphasis mine):

Children between the ages of seven and twelve, on the other hand, have some adult characteristics, such as mental mapping, but they don’t have adult judgment. They don’t ordinarily have the strong ability to control emotional responses and to reason through their situation. They panic and run. They look for shortcuts. If a trail peters out, they keep going, ignoring thirst, hunger, and cold, until they fall over. In learning to think more like adults, it seems, they have suppressed the very instincts that might have helped them…a little knowledge is dangerous.

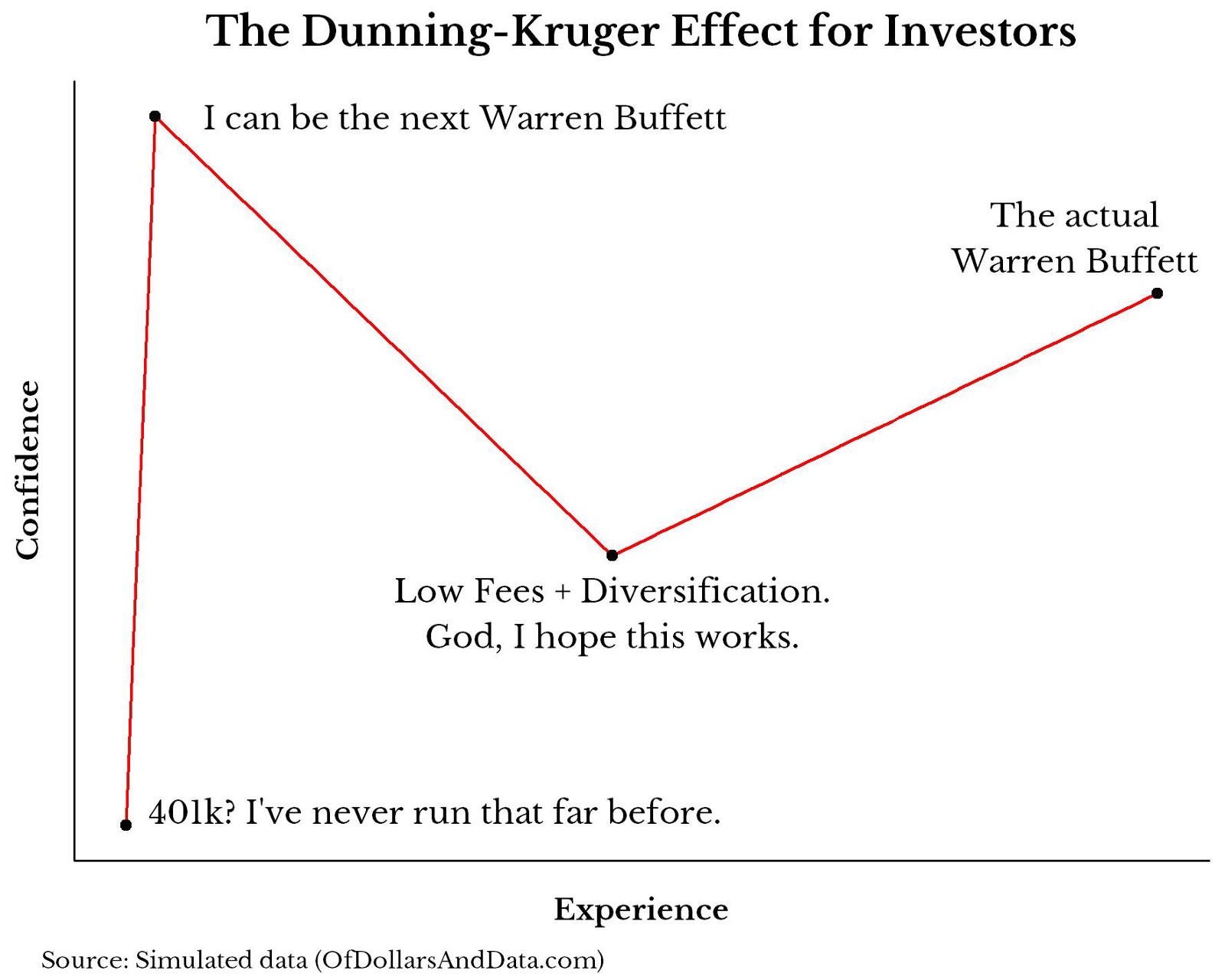

This idea is incredibly powerful because there is evidence that having a little knowledge on a particular topic can lead to vast amounts of overconfidence. This overconfidence, in turn, can lead to bad decision making. In psychology, this is known as the Dunning-Kruger effect, or the cognitive bias in which individuals with low ability perceive themselves as having high ability.

Dunning and Kruger found that after gaining a small amount of knowledge in a particular domain, an individual’s confidence soared. However, when that individual was provided with further training, they were better able to assess their skills and their confidence dropped. It was only once their experience approached that of an expert did their confidence rise again.

If we had to imagine an investor’s confidence as they gained experience, it might look something like this:

I can tell you that I am sitting comfortably in the “God, I hope this works” category. All jokes aside, overconfidence is the most dangerous investment bias out there because it is so prevalent and hard to recognize in your own behaviour. Don’t believe me? Consider Jason Zweig’s question from Your Money and Your Brain:

Just ask yourself: Am I better looking than the average person?

You didn’t say no, did you?

I could ask you hundreds of other questions assessing your abilities in various domains and you are likely to believe you are above average in many of them. In fact, Zweig’s research found that roughly 75% of people believe they’re above average regardless of the skill that is being assessed. Driving? ~75% believe they are above average. Telling jokes? ~75% above average. Intelligence tests? You guessed it. This was true despite the mathematical fact that only 50% of people can be above average (technically median, but you get the point).

Why does this matter to you as an investor? Because almost every epic investment blunder in history was the direct result of overconfidence. Long Term Capital Management were confident that bond spreads couldn’t widen beyond a certain point for a prolonged period of time. Investors during the Dot Com Bubble thought that the internet was the future of the economy (Marc Andreessen argues that these investors were right, just too confident too early). When the treasurer of Orange County’s investment fund was asked how he knew interest rates wouldn’t rise, he replied:

I am one of the largest investors in America. I know these things.

His fund filed for bankruptcy within a year.

However, don’t let the pros take all the credit, overconfidence can hit closer to home as well. I remember years ago spending an hour or two reading financial statements on an individual stock before buying it. That’s all it took. One hour and I put a few grand into a single stock that ended up underperforming the S&P 500. I’ve honestly spent more time shopping for the right pair of dress shoes.

At this point, if you haven’t admitted that you have fallen victim to overconfidence, I am telling you that one day you will. You won’t even realize it either. However, there are a few things you can do to prevent this.

How To Spot Your Own Overconfidence

So, you’ve made a decision and want to know whether you are being overconfident? Here are a few suggestions:

- Ask yourself how long you have thought about the decision. If you were exposed to a topic relatively recently, the data suggests you are more likely to be overconfident. Do more research first.

- Get opinions from other sources with opposing viewpoints. If your decision is reasonable, it should be able to stand up to a fair amount of scrutiny.

- Question everything, just like a small child would. This recommendation comes from Your Money and Your Brain and it closely relates to the survival stories I told earlier. If you keep asking yourself “Why?” you may realize that your logic has many holes in it.

- Diversify. No one ever went broke by being underconfident and allocating less capital to a position. No one ever got filthy rich doing this either, but that conversation is for another time. Side note: The word “underconfident” isn’t recognized by Medium’s spell check. See my point?

While these ideas are not guaranteed to eliminate overconfidence, they can help you recognize when a little bit of knowledge might be dangerous. Lastly, if you are interested in other behavioural biases that affect investors, in addition to Zweig’s book, I also recommend James Montier’s The Little Book of Behavioral Investing. Thank you for reading!